Every word and every phrase evokes a frame. But what is a frame? A primer on framing and how you could be working against your own interest.

Before I begin, here’s a simple instruction: don’t think of an elephant.

Chances are you now have an image of an elephant in your head. It’s a trick George Lakoff, a cognitive linguist, uses to demonstrate that almost all thought is automatic and unconscious.

Our brains receive and process information so quickly we often have little control of the things that pop into our minds when we observe things or receive messages. Political operators and advertisers know this very well.Our brains make mental shortcuts to help us organise the information we receive.

These shortcuts and associations are known as “frames”.

What’s a frame?

A frame is a structure that helps us make sense of the world. Frames are made up of words, phrases, images and scenarios; these words and phrases activate pre-existing frames in our brain. A very basic example of a frame is a restaurant. When you hear the word “restaurant” other words and images are evoked such as: food, waiter, knife, fork, kitchen, table and scenarios like ordering from a menu. We know the menu is given to us at the beginning of the meal and the bill at the end. These words and scenarios form a narrative in our brain that are known as frames.

You can’t avoid frames. George Lakoff says, “all thought is physical”. That is to say — the associations our brain makes with certain things can’t be erased or easily ignored because our brains are wired to associate certain things together.

Here’s a quick exercise. Think about what comes to mind when you read the following words:

- airport;

- elephant;

- supermarket;

- war.

“Airport” probably evoked words and images like: plane, check-in, pilot, security and waiting to board. The airport frame is less likely to evoke words like polar bear, boat or tree. “Supermarket” likely evoked words and images like aisle, checkout and trolley.

Moral 1. Every word evokes a frame.

A frame is a conceptual structure used in thinking. The word elephant evokes a frame with an image of an elephant and certain knowledge: an elephant is a large animal (a mammal) with large floppy ears, a trunk that functions like both a nose and a hand, large stump-like legs, and so on.Moral 2: Words defined within a frame evoke the frame.

The word trunk, as in the sentence “Sam picked up the peanut with his trunk,” evokes the Elephant frame and suggests that “Sam” is the name of an elephant.Moral 3: Negating a frame evokes the frame.

Moral 4: Evoking a frame reinforces that frame.

Every frame is realized in the brain by neural circuitry. Every time a neural circuit is activated, it is strengthened.

The same applies to issues. When you hear phrases like “tax relief” and “climate change” you might not think anything of them. But this is the language that conservatives have invented or co-opted to pursue their agenda. They tell a story because of our preexisting associations to those words and create a frame in our minds.

Frame: global warming or climate change?

Conservatives know that “climate change” sounds less scary than “global warming”. We know this because Frank Luntz, a Republican Party strategist, advised George W. Bush to use the term climate change. The leaked memo says:

It’s time for us to start talking about “climate change” instead of “global warming”…

As one focus group participant noted, climate change “sounds like you’re going from Pittsburgh to Fort Lauderdale.” While global warming has catastrophic connotations attached to it, climate change suggests a more controllable and less emotional challenge.

Luntz was advising the Republicans to acknowledge global warming was happening, but call it something else. Something less threatening, less urgent, less important. This is framing. You take the same issue — the planet’s temperature rising — and communicate that issue in a way that persuades people you have the best ideas, approach, whatever.

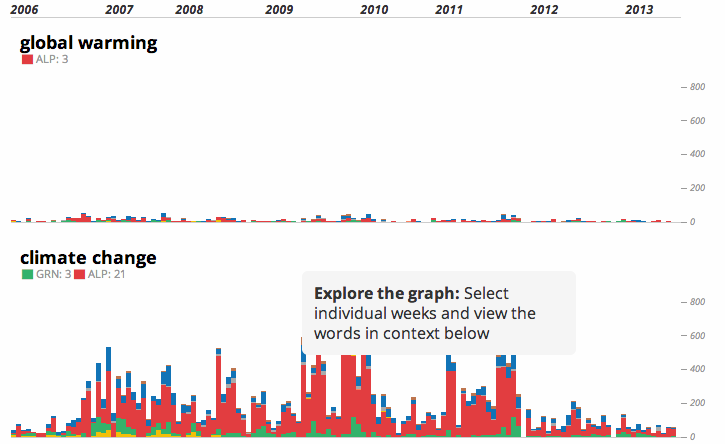

The aim of framing is to get “the other side”, the media and the public using your language so it serves your purpose. Done well, they won’t even know that they are using the language that is serving your interest. It has worked. Environmental organisations use climate change all the time. A tool developed by The Global Mail shows that in Australia “climate change” is used more often than “global warming” by a considerable margin. It serves as an effective example of framing an issue.

Tax frames

Progressives are not good at talking about tax. They all too easily pick up the language of conservatives because they have not formed their own clear narrative on taxes. Lakoff says taxes should be framed as patriotism:

Taxes are what you pay to be an American, to live in a civilized society that is democratic and offers opportunity, and where there’s an infrastructure that has been paid for by previous taxpayers. This is a huge infrastructure. The highway system, the Internet, the TV system, the public education system, the power grid, the system for training scientists – vast amounts of infrastructure that we all use, which has to be maintained and paid for. Taxes are your dues – you pay your dues to be an American.

But that’s not the language progressives use. They use the language of the conservatives as the following examples show.

Tax relief

It got picked up by the newspapers as if it were a neutral term, which it is not. First, you have the frame for “relief.” For there to be relief, there has to be an affliction, an afflicted party, somebody who administers the relief, and an act in which you are relieved of the affliction. The reliever is the hero, and anybody who tries to stop them is the bad guy intent on keeping the affliction going. So, add “tax” to “relief” and you get a metaphor that taxation is an affliction, and anybody against relieving this affliction is a villain.

“Tax relief” has even been picked up by the Democrats. I was asked by the Democratic Caucus in their tax meetings to talk to them, and I told them about the problems of using tax relief. The candidates were on the road. Soon after, Joe Lieberman still used the phrase tax relief in a press conference. You see the Democrats shooting themselves in the foot.

Death tax

“Death tax” is a term that Luntz picked up in focus groups. The alternative phrases being “estate tax” and “inheritance tax”. When Luntz asked participants which of these taxes they would like to see eliminated “death tax” won easily. Why? An inheritance tax sounds like a tax on money and assets going to inheritors (usually children) of an estate. It’s a small amount taken from an often large pool of assets they will receive. “Estate tax” works in a similar way.

“Death tax” is a different kettle of fish. This communicates a government that has its hands in the pockets of people even after they die — after they’ve paid tax all their adult lives the government is fleecing them one last time. Same law, different frame, completely different response from people.

Carbon tax

Former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard made a big mistake in framing Australia’s price on pollution to tackle global warming as a “carbon tax”. I’ve written about this mistake before. To her credit Gillard admits it was a mistake:

I erred by not contesting the label “tax” for the fixed price period of the emissions trading scheme I introduced. I feared the media would end up playing constant silly word games with me, trying to get me to say the word “tax”. I wanted to be on the substance of the policy, not playing “gotcha”. But I made the wrong choice and, politically, it hurt me terribly.

But why was it a mistake? Carbon tax was the wrong frame. It gave Tony Abbott the fuel he needed to deceive the public by combining the fear of higher taxes with their lack of understanding about what carbon is. The combination of “carbon” and “tax” became a lethal cocktail of fear and confusion. Tony Abbott framed the debate on a carbon tax. The media and the Labor Party reinforced this frame constantly and the public picked it up.

What could the Labor Party have said instead? They could have followed the advice they were given and said it was a “price on pollution”. People don’t like pollution and they think we should reduce it. Labor chose not to evoke the “pollution is bad” frame and shot themselves in the foot.

All this is not to say that progressives shouldn’t avoid the term “tax”. Rather it needs to be framed it in a way that makes people’s lives better as Lakoff suggests. Our taxes pay for the things we rely on every day and others will rely on in the future.

Using frames

You may read this and think frames are manipulative or deceptive. They can be. But we can’t avoid them. Frames are everywhere as the restaurant, airport and elephant examples show. The question for communicators is “what frame/s are you using?” If you don’t know it’s worth taking a moment to think about how you have framed your communications. To be effective you need to ensure you are reinforcing a consistent frame in every channel of communication.

If you’re not aware of which frame you are using you may be working against your own interests. You may be reinforcing the frame of the “other side” or those who have different views to that of your organisation. Are you using the same language as those who hold the opposite view to your own? If you are you might be using a frame that serves their interest and not yours.

If you have any examples of effective framing or would like feedback on your own material feel free to post them in the comments or get in touch.

Further reading

The following resources I’ve read or watched and can recommend. Some of the links are focused on politics but the principles and thought can be applied anywhere.

- George Lakoff- Don’t Think of an Elephant (short book and excellent primer)

- Frank Luntz – Words that Work (book)

- Drew Westen – The Political Brain (book)

- My review of The Political Brain

- Lakoff, Luntz and Westen discussing the language of political candidates (YouTube)

- Frameworks Institute – Changing the public conversation on social problems (Presentation)

- Finding frames – A six month study and report on how to engage audiences in global poverty (PDF)

[…] phrases activate pre-existing frames in our brain. To understand frames I recommend you read my short primer on framing. To reframe a question you need to understand what a frame is.From my […]